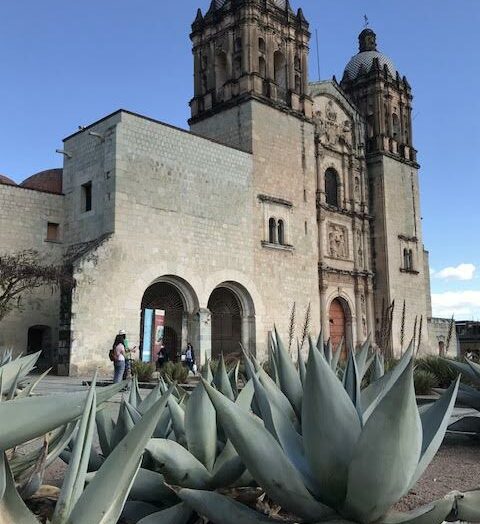

On the south side of Mexico City, Mexico, is the vibrant and cultural neighborhood of Coyocán. In a past adventure, I have walked its tree-lined streets and marveled at its Indigenous Artisan Markets but on that trip, I wasn’t able to obtain a ticket to the home of the area’s most famous resident, Frida Kahlo.

On this trip through Mexico City, I planned ahead, securing a ticket to her infamous “Casa Azul” or “Blue House”. This was the place where Frida spent her early years, and then later, the years of her marriage with world-renown muralist Diego Rivera. It was within these walls, that she designed an inspired life of creativity, community, and self-reflection. The Frida Kahlo Museum was established by a trust of Diego Rivera to preserve their home and her collections. It is a wonderful legacy of these two artistic wonders.

The passionate romance of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera survived a marriage, divorce and remarriage while living in various homes, including Casa Azul (the “Blue House”) in Coyocán, Mexico City.

When I first entered the Casa Azul, I was immediately struck by the gardens. Taking up almost a city block, the house surrounds at least two sides of this immense courtyard where Frida strolled, sat and painted her birds and other garden animals. The gardens also provided the backdrop for many social occasions where well-known friends and artists from around the world gathered for political and intellectual soirees.

Upon entering the house, a wonderful display of signs helped me to understand why Frida Kahlo lives on today.

From a young age, two realities shaped her life. First, she was always encouraged to be curious. Her father was a photographer and he nurtured her artistic interests, especially in nature. She never stopped creating and pushing the boundaries of creativity.

At the same time, health issues constantly plagued her life. At the age of six, she contracted polio which withered her right leg and gave her a life-long limp. She began wearing several pair of socks and shoes with different heals to make her legs look equal. She ended up just wearing long dresses to cover her disability.

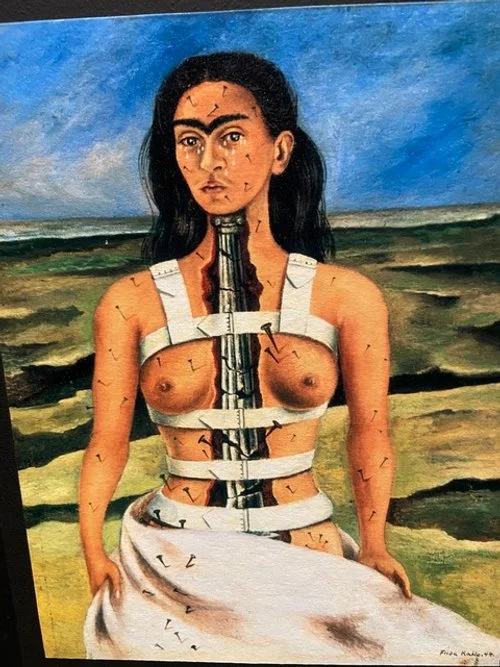

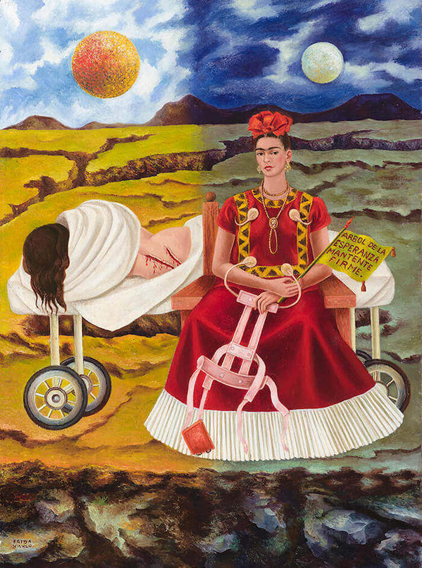

Then, at the age of 18, she miraculously survived a serious bus accident which broke her spine and pelvis, making it impossible for her ever to have children. Over the next years, she consulted with the best doctors and pursued over 22 different surgeries, including much later in life, a leg amputation. Sometimes after these surgeries, she was able to walk. Sometimes she was bound to her wheelchair or bed.

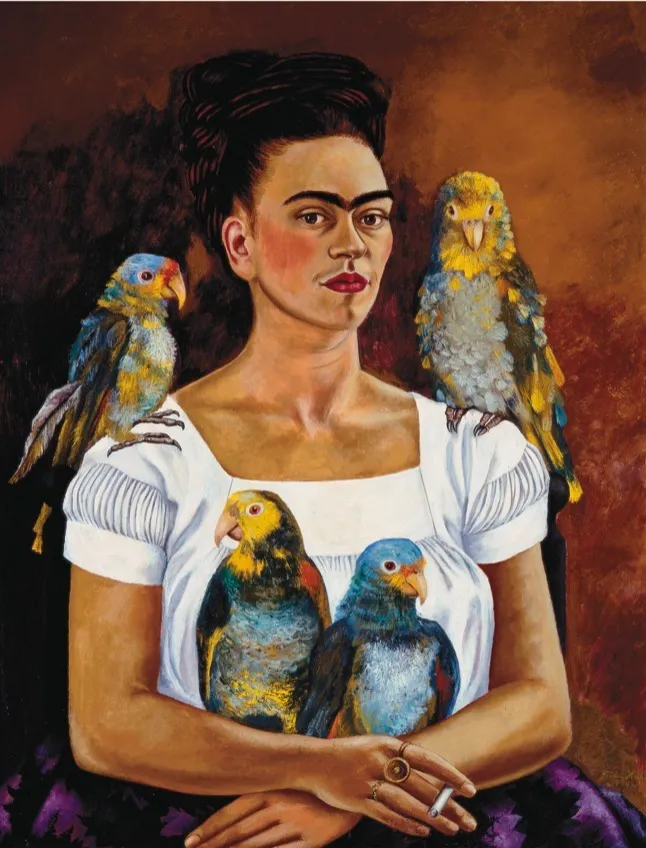

What’s amazing about Frida is what she did with the life she was given. She didn’t waste her time wallowing in pain. She created. She started by painting on her corsets and body braces. Her mother installed a mirror above her bed so that she could see herself completely. She used this opportunity to explore her body, her femininity, and paint vulnerable self-portraits expressing her pain and her dreams. For example, she sometimes painted herself with doves or butterflies in place of her body parts, imagining the freeing of herself from her broken body.

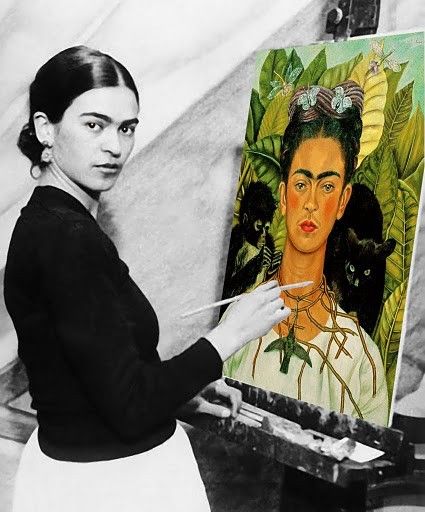

She commissioned a vertical easel attached to her wheel chair so that she could also sit and paint the things surrounding her life. These works are clearly inspired by historic and colorful Mexican Folk Art.

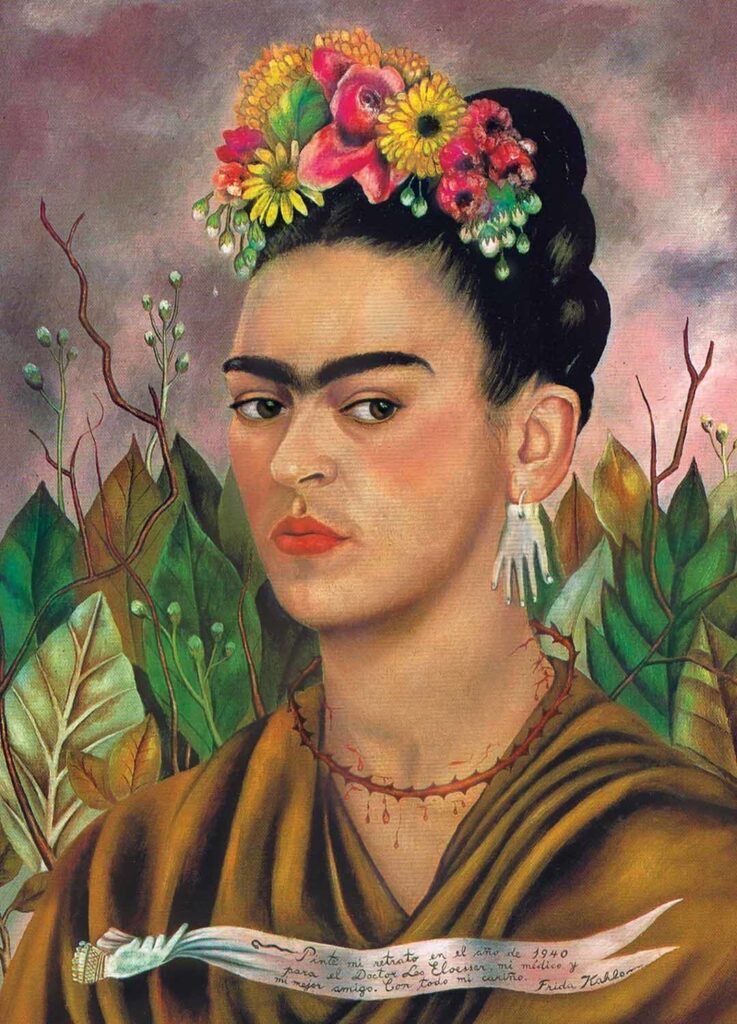

Through the 1930’s and 1940’s, her strong sense of heritage and deeply moving self-portraits landed her much acclaim in the art world and when she traveled outside of her home, she adopted the cultural clothing of her mother’s ancestry. The dresses she used were Tehuana, which is from the matriarchal Zapotec culture of Tehuantepec, Mexico. This style often includes an embroidered huipil or square-cut blouse, a long skirt or enagua, and a shawl called a rebozo. Her jewelry and the corona de flores gracing her head was always stylistically designed to accentuate her outfit. After all, she was an artist.

I had always learned that the iconic Indigenous image she projected was due to her national pride and independent spirit bucking contemporary clothing and make-up trends. It also distinguished her in the art world. But that was only partly true.

At the Casa Azul, I learned that she partly adopted this style for comfort. The drapy clothing hid metal corsets and braces holding together her torso and legs. She also used the intricately designed neckline of the blouse, jewelry and crown of flowers to draw a viewer’s attention up and away from her broken body into her deep eyes and natural beauty of her face. For these reasons, she became, and continues to be, an icon for nonconformity and traditional beauty standards.

I wandered the rooms of the Casa Azul, fascinated by this strong and extraordinary woman. Her kitchen, her art studios and the bedrooms of the house are mostly as she left them.

In 1954, at the age of 47, Frida Kahlo’s spirit finally left her body behind.

In the gardens of the Casa Azul, an altar honors her legacy.

I feel so fortunate to have walked in the place of Frida Kahlo, to appreciate all that she endured and to learn from her passion to live the life she was given to live. Using her brush, she gave voice and power to women, political ideas, Indigenous cultures, and folk art from around the world. Thank you Frida, for all you have given us.

Please note, almost all of the photographs contained in this post are copied off the internet. I obviously didn’t meet Frida Kahlo or view all of these important works.

Thank you to my sister Julie, who traipsed all over Mexico City with me for three days, enjoying all it had to offer!

Dana Harden

For my 70th birthday, my daughter took me to Mexico City – we stayed at a lovely Airbnb in Coyocan for part of our trip, and visited Casa Azul – what a beautiful, amazing place!

Debbie

I have always adored the life and history of Frida Kahlo. Frida is one if my favorite films. I would absolutely enjoy being in the presence of her spirt at Casa Azul I have bee traveling the world with my two best friends fir over 30 years. I need to renew my passport so I can go! This is one of the best renditions I’ve seen. A few years ago I also found an original piece of art in a thrift store devoted to Frida. It is raw but awesome.

Hope to visit Casa Azul someday I’m 69.