The opinions in this post are strictly my own, based on my lived experiences traveling and working in South American countries. Thank you for your interest.

Traveling in Argentina and Chile has been a very interesting experience. Both of these countries are large, developed and politically democratic. But other than the mountain range they share across their borders, they are really very different: different foods, different traditions, and really different people.

Although Chile and Argentina have similar Indigenous groups and they both have large populations of Europeans who historically migrated to their countries, their people are still drastically different. You notice it immediately when you cross the border. It’s their attitudes, how they dress and carry themselves, and their outlook on life.

Generally, Argentinians are gregarious. They laugh and tease each other. They are overwhelmingly polite and appreciative to anyone that crosses their path. They’re inquisitive. They are easy to talk to. They seem to be really positive people.

Chileans, on the other hand, are mostly quiet and reserved. They nod. They stare. They talk quietly among themselves in public. They rarely asked me a question or engaged me in any kind of conversation. While groups of teenagers can sometimes get a little more lively, walking down the street in Chile is definitely a grittier experience. Often, my smile didn’t even disarm them. Chileans are not unkind, they’re just not warm.

Two counties, similar populations, similar histories, but really different people.

Why is that?

In today’s post, I’m not going to introduce you to a place. Instead, I’m going to attempt to unpack some very complicated history (which I do not totally understand) to help provide a context for what I’m experiencing. Then, I’m going to share with you how this history lesson has given me a little perspective about the history and the future of my own country.

Stick with me.

Argentina’s Dirty War

When I first arrived in Argentina, I noticed immediately that every park and government building proudly displayed monuments to the citizens they’ve lost in different wars over time. For example, I frequently saw homages to the “disappeared” or “desaparecidos” of the “Dirty War”, which is what they call the time when Argentina was under the rule of an oppressive dictator. In every town I visited in Argentina, there was always a monument with a list of names of local citizens who disappeared during that time. If I didn’t see a monument, I saw posters of faces, murals expressing a collective anger, or promotions for community museums and organizations to help process their past together. Argentinians, it seems, are determined to keep the memory of their loved ones alive. They are proud people, with a strong national identity and they don’t want to forget this part of their history.

That said, I was warned emphatically, not to outright ask an Argentinian about their experience during this time period. They don’t like to talk about it openly because it was so horrible. But I’m curious, and while I tiptoed around this topic with a few different Argentinians I’ve been able to glean a little of the story. One older man just shook his head and stared off into the distance. You can’t imagine, he said to me, how an entire generation has been psychologically destroyed by the fear of being kidnapped in the night.

From those few discussions and published summaries on line, this is what I understand about Argentina’s Dirty War:

In Argentina, after several tumultuous years and the strong-hand, leftist politics of Juan Peron, a three-man military junta seized power of the government in March of 1976 and established Lieutenant General Jorge Rafaél Videla as their first leader.

Immediately, the Dictatorship closed congress, initiated strict curfews, imposed censorship, banned trade unions and brought state and municipal governments under military control.

In an effort to control dissidents, it is estimated that between 10,000- 30,000 people were kidnapped, tortured and killed within the walls of hundreds of clandestine detention camps set up around the country. Initially, Argentina’s Dictatorship received support from the outside world because they claimed they were fighting a “civil war” against leftist guerrillas. But, it was the women of the country (called La Madres (or Mothers) de Plaza de Mayo, who started to speak out and garner international attention. They famously gathered each Thursday around the Plaza de Mayo in front of the government palace in Buenos Aires to advertise the names of their children and grandchildren who had gone missing. These children became known as the “desaparecidos”, or disappeared. In addition to the powerful voices of the “Madres”, the strong liberal foundations of this country united the people together against the regime.

Finally, with growing evidence of the horrid civil rights violations, and a disastrous war in the Falkland Islands (known in Argentina as the Malvinas), the Dictatorship succumbed and held a democratic election in 1982, which restored several rights to its people. Since then, some justice has been served as many in the regime have been prosecuted and served jail time for their human rights abuses and war-time atrocities.

In the streets of Argentina, it is common to see signs, memorials, and murals paying homage to those who disappeared during the Dictatorship, as well as those who fought to find them and keep their memory alive. Argentina has also converted many of the secret detention centers into museums (where political prisoners were held and tortured) to relate the history of what happened within the walls of those prisons.

Chile’s Dictatorship

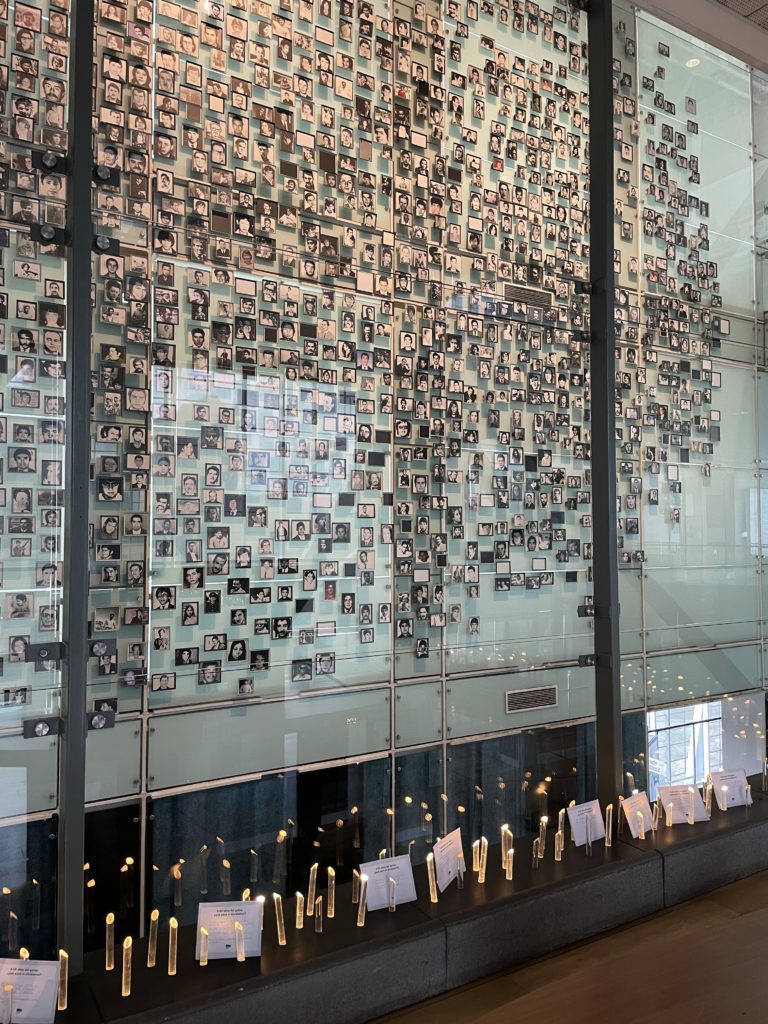

While traveling Chile, I had the same desire to learn about their history, but frankly, I haven’t been able to have an in-depth conversation with many Chilean-born citizens. For those Chileans who have talked to me, they all said that the time of the Dictatorship changed everything about who they are today. In their words, it’s the reason why they are “closed”, “distant”, and “untrusting”. Thanks to Google, and a fantastic “Museo de la Memoria y Los Derechos Humanos” (Museum of Memory and Human Rights) in Santiago, this is what I know about Chile’s Dictatorship:

On September 11th of 1973, a military junta headed by Augusto Pinochet, overthrew the democratically elected socialist government of Salvador Allende in a coup d’état. The military was bowing to pressure from conservative leaders and international allies (including the United States’ CIA) who were worried about Allende’s wealth distribution policies, a pending economic crisis and the possibility of socialism spreading throughout South America. This was their justification to seize power and form a Dictatorship in order to forward their own agenda of “National Reconstruction”, which was founded in principals of capitalism and westernization.

A museum exhibit describes the terror that ensued:

“After the coup d’état, a period marked by persecution, repression and censorship began. From the very beginning a policy of banning books, records and posters with images and titles considered dangerous was implemented. Police and the military stormed houses, universities and work places searching for reasons to interrogate or detain people.”

The museum signage described that the Military Dictatorship maintained its power through “a systematic suppression of political parties and persecution of dissidents. They put an end to all labor, professional, community, cultural, student and even athletic organizations… And they controlled the movement of people by enforcing a strict curfew which restrained daily life for the citizens of Chile.”

All of the enacted policies were designed to repress free ideas and institutionalize fear among and between the citizens.

By the time the regime fizzled in 1990, over 3,000 people were dead or missing, around 30,000 people had been tortured in clandestine detention centers, and over 200,000 Chileans had been driven into exile and forced to live elsewhere around the world.

Because powerful conservatives and the business establishment benefited financially during this time, they supported the economic policies of the regime. In fact, some argue that Chile made significant economic progress during this time and deny that the later years under the “Dictatorship” were really that bad. Their lives in fact, didn’t suffer very much. Because of this, Chileans are still living under the constitution written during the Dictatorship and very few of the war criminals have ever been punished, including Pinochet himself.

In all my travels around the villages of Chile, I’ve seen very few monuments to the victims, or to this period in their history. Chileans, as I understand it, don’t generally talk about history or politics – probably because it’s too divisive.

One morning I was having breakfast with my Chilean friend Yetzabel. Because she is my friend and I knew she trusted me, I broached the subject about the differing viewpoints of the Dictatorship. Without realizing it, everybody in the restaurant got really quiet and started listening to our conversation. After a few minutes, one young woman approached our table with tears in her eyes. She was so upset that we were discussing this horrible time-period in an objective way and she implored me to not cause more suffering by digging deeper into the topic.

All of this tells me that as a community, Chileans have not processed their past. It seems that they still don’t trust each other, they don’t trust outsiders, and they don’t trust that their future is going to be any different.

From other people, I was also told that this time period is not included in Chilean history books. It is up to the individual teachers of public schools whether or not they include it into their curriculum. Students in private schools do not get this history lesson at all, because, generally, their parents are of the upper conservative class, and they want to control the story of what their children learn. That said, in the capitol of Santiago, the Museum of Memory and Human Rights thoroughly covers the Dictatorship and the human atrocities in detail. And the artists of Valparaíso, a city known for its dissidents and free-thinking university population, has turned the town’s historic prison and detention center into a cultural arts center, community garden space and memorial to the political prisoners who were imprisoned and tortured there. In both of these locations, I noticed tour groups of students obviously learning something about this history.

The Valparaíso Cultural Park is now a vibrant community arts center in the former city prison.

My Take-Away

As I wandered the Human Rights museum, I kept asking myself, how does this happen? How can people be so cruel to other humans? How can they do this to their own people?

Display after display, I started to piece together an answer, a pattern of how such a thing can really happen. This is the same pattern of behavior that changed both of these countries forever.

Step 1. It starts with someone- a leader or a group- believing that their ideas are absolutely right.

This is righteousness.

Step 2. This leader starts making up lies to justify their ideas. Many times the stories are to discredit their enemies… “who they REALLY are, what they’re REALLY doing”. The purpose of this rhetoric is to divide and develop distrust among anyone who may believe differently. The leader’s thought is that if the public only hears confusing stories and begins to doubt everyone else, then they won’t unite against him.

Step 3. The leader and his supporters start censoring books and news, controlling what the public reads and doesn’t read, what media they listen to, what stories they hear. An uninformed public is easier to manipulate.

Step 4. Then, they make laws to control who gets to vote and the process of being able to vote. The purpose of all of this is to limit the power of their opponents.

Step 5. After that, it’s not so hard to convince others that the Constitution needs a rewrite. So they, and their friends in the military and in the courts, can maintain their power into the future.

Step 6. Now that the people are ignorant and powerless, the leader -and his supporters- can do anything they want to do…. kill, torture, imprison… because it’s all in defense of what they know is right. Righteousness can justify anything.

When you think you’re right, it gives you reason to not listen, learn from, and understand another point of view.

This is how a Dictatorship is born.

Argentina had a Dictator from 1976 to 1982. Chile had a Dictator from 1973 to 1990. In the case of both of these countries, they went from democratically elected leaders to Dictatorships overnight. In each case, the six steps outlined above were the foundational steps that allowed for a coup d’état to happen, and allow the leader to keep the power for years to come.

If you’ve never traveled to a country who has experienced the actual disintegration of their Democracy, or watched people take to the streets to fight for their rights and the future of their livelihoods, it’s very easy to consider that the United States is immune to such things. After all, our Democracy was founded 200+ years ago. It’s historic. It’s stable. But If you widen your lens to really think about the things that are transpiring in our country today, you might see some similarities to what I’ve described here.

I love the country of my birth, but travel has changed my perspective. I’m worried about the United State’s current health and well-being. I’ve come to understand how fragile Democracy can be. If we want to keep it, we need to pay attention, so history – anyone’s history- doesn’t repeat itself.

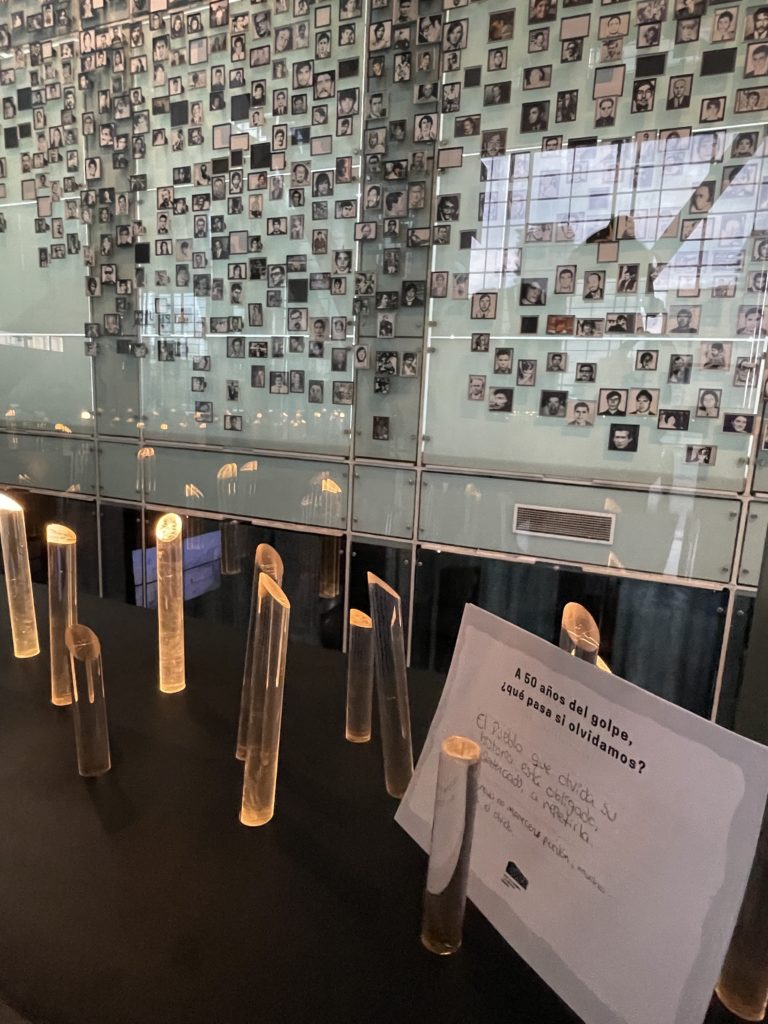

A Chilean citizen wrote: “A community that forgets their history is obligated to repeat it.”

Eliza

This is such an informative, reflective post Becky. Having never learned much about the histories of Chile and Argentina I found this fascinating and very helpful. There does seem to be so much healing and openness and ability to move forward in communities that directly deal with the horrors of the past. I am reading the book Revolutionary Nonviolence about the methods of James Lawson’s activism and there is a segment that talks about healing and open conversation as a key part of building a beloved community. Thanks for this great post and hugs to you!

Tom

Great post Becky, thank you for your history lesson and insights!

Andrea Scharf

Hi Becky! Thanks for this excellent discussion of the perils of maintaining democratic institutions and the review of history of Chile and Argentina. If readers are interested in an intimate look at Chile, i recommend Isabel Allende’s novel, Largo Petalo de Mar (the long petal of the sea). I read it in Spanish because my teacher in San Miguel de Allende chose it for me–a brilliant choice, combing my interest in history with language study. The novel starts in Spain, in 1936, as the fascist war against the legitimately elected Republican govt gets started. Ultimately Franco and the right wing won and the Republicans fled. Some ended up in Chile, with the help of Pablo Neruda. When the same horror happened again, with Pinochet’s fascist right wingers, the main protagonist of the story ends up in a concentration camp before finally fleeing to Venezuela–which at the time was a fairly open anything goes country, propserpous, lively etc. My teacher posed the question–why are Chilenos so quiet and repressed? She blamed largely on the conservative upper classes and a very conservative culture of Catholicism and business. There are also a number of films about The Disappeared in Argentina–Cautiva (Captive) is one that i remember. The horrors of the Dirty War, many revealed by the mothers and grandmothers who demonstrated in the Plaza, seeking information about their sons and daughters who were brutally murdered, including pregnant women, whose babies were also “disappeared” and adopted by the families in power. That happened in Spain too. Ugly history, and yes, we’d better pay attention or it could happen here….cuidado!!

Becky Wandell

Thank you so much Andrea for offering some more context and suggestions for future learning about this incredibly complicated, interesting and important topic! I really need to read that book!

Michael Huelshoff

I think you hit the Chilean part of this pretty much spot on. I always thought Constable and Valenzuela’s book, A Nation of Enemies, offered a pretty compelling explanation for the problem. Their argument in brief is that Pinochet, not being from the upper classes that dominated (and continue to dominate) Chilean society for so long, viewed his contemporaries with utter contempt. Indeed, he purged, and even murdered, many of the aristocratic members of the military, and arrested leaders from many parties (including some on the right). And of course he engaged in a spree of extrajudicial killings of not just politicians on the left but also musicians, film makers, poets (Neruda), etc. In short, Pinochet believed in nothing, and used terror to force that on Chilean society. Hence the title of their book. Pinochet believed in nothing but his own power and used it to steal his way into the wealthy classes. I always thought that it was telling that much of his wife’s wealth came from a chain of butcher shops.

I don’t know as much about the Argentinian dictatorship, which was also wedded to violence and terror, but I understand that one difference between the two has to do with the treatment of civil society. Both dictatorships banned political parties, arresting and killing some of their leadership. In Argentina, civil society groups were independent of the political parties. In Chile most were tied to political parties. Thus, when democracy was restored Argentina had a functioning civil society and Chile did not. Indeed, the nihilistic nature of the Chilean dictatorship made it hard to restart civil society. Further, what the Chileans had (and the Argentinians largely did not) was a somewhat successful market economy, which itself emphasizes competition and atomization of society. By this argument, remembrance, confronting the past, was easier in Argentina than in Chile—the social groups who demanded it were there. Further, the transition to democracy in Chile was slow. Pinochet wrote into law a lot of provisions to protect himself and his supporters and regularly threatened to seize power again, while in Argentina the generals were quickly swept from power (Malvinas war).

Your reference to events in the US is telling. I share many of your concerns. I was shocked to see that the most recent killer in the mall in Texas was wearing a patch that read “RWDS,” which I understand stands for “right wing death squad” and is a direct reference to the Caravan of Death. It is also very disturbing to see Trump supporters like the Proud Boys wearing t-shirts that read “Pinochet did nothing wrong,” and include pictures of helicopters (a favorite execution method of the Pinochet dictatorship was to tie their victims up in chains and fly them out over the ocean in helicopters and kick them out while they were still alive. Fisherpersons still occasionally drag up chains).

Becky Wandell

Thank you so much Michael for bringing more depth and insights into this discussion. I really appreciate learning from your perspective and your nearly life-long experience and connection to Chile. It was my first discussions with you that gave me enough understanding of the situation to want to write this post. Clearly, there’s so much to learn from this history, and so much we need to pay attention to for our future!