Hundreds of spiritual worshipers already in the water, above and all around clinging to the hillsides of the canyon, their cell phone flickers giving them away. Hundreds more in front of me, carefully stepping their way down the rocky path to the base of the falls. Whistling, hooting, laughing, and the deep low belch of the el churo, the conch shell. Pushing forward again, searching for my guide in the dark. He wears the Huma, the rainbow colored two-faced mask. Like so many others, he is warding the negative spirits away. Finally, we reach the bridge, the base of the falls.

Peguche.

Her mist pelts my face. Her energy and the energy of the masses reverberate through me under the light of the half moon. We make a spot for ourselves among the crowd and in my 1-foot square, I peel off my layers of clothes. The damp, cold air gives me a shiver as I get down to only my underwear, just like the strangers next to me. Pedro hands me branches of the three herbs held sacred for this ritual bathing. The spines of one cut into my palm. I will use them to beat my skin, ridding my body and my life of all the negative energy. But first I must ask Pachamama, or Mother Earth, for her permission to enter the water, to be taken into her care.

It’s time. It’s midnight. The 12 most sacred and powerful minutes are upon us now. I step carefully on the rocks and wade into the frigid flow. I slip, fall in, and the current starts to take me away. I find my footing. I stand, unable to breathe from the shock of this emersion. I find a secure foothold, and I lean against the power of the water and reach a calm. I look up.

The moon light is gloriously reaching down through this canyon, kissing my skin. The stars twinkle above, offering their encouragement for what I must do. I start to whip. I ask the moon, my Luna, to please help me rid myself of all my negative energy; my grief, my sometimes overwhelming sadness for a life lost, my fear of going forward alone in the world, my worry about never experiencing love again, in the way I once knew. I ask the moon for the strength to help me to let go and move on. I ask her for the strength to find who I am on my journey, for the awareness to live intentionally, appreciate the now and look forward to the unexpected in my future. With my hands raised to the beauty of the moon, her skies, the water, the earth and all of the blessed humanity surrounding me in this moment, I prayed for a future where acceptance will empower me, light my way and help me be the love and light in this world that I was born to be. And in the power of this moment, I notice my soul feels lighter, happy, cleansed, and ready for the new year.

They were.

I just know it.

December Solstice: Kapak Raymi celebrates the caring for the plants

March Equinox: Pawkar Raymi celebrates the season of blooming

June Solstice: Inti Raymi celebrates the Sun for the harvest

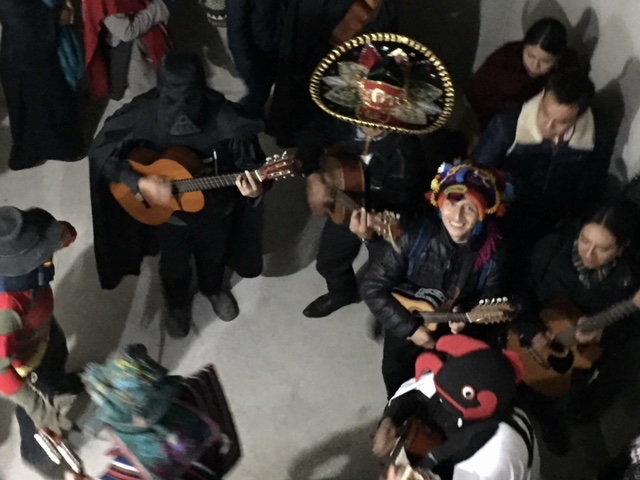

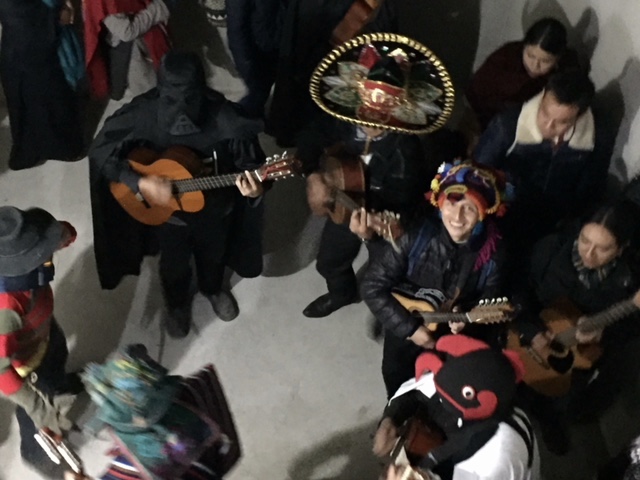

In Ecuador, Inti Raymi is the largest of all the festivals and each small community offers their own take on the celebrations that last all summer through August. The first three nights of the new Solstice are considered the most powerful and singing and dancing are in full force for all Indigenous families. For weeks, I’ve been hearing so much about the power of this weekend, but as a Gringa, I wasn’t sure how my intrusion into these sometimes private celebrations would be received. So, after asking many people, I finally got connected with Pedro, an Indigenous man who likes to share his culture with others. For a small and very reasonable price, he invited a few of us Peace Corps volunteers to join his family and participate in the purification bath on Friday at the waterfalls in Peguche, and again on Saturday night in the nearby Indigenous city of Otavalo. For this second night of celebrations, people donned masks, wigs and costumes, and paraded through the streets from house to house for a long night of music, drinking and dancing. As we left each house, the hosts joined us and the group got larger and larger as the night went on.

|

| Pedro played the Mandolin as we formed an ever-intertwining circle around him. |

| Chicha is a fermented drink make from corn. Its very sweet, and often served in a half shell of a gourd scooped from a bucket or poured from a pitcher. Everybody sips from the same vessel. |

| Fireworks were a part of the entertainment in the streets. |

|

| We met several other groups parading through the streets as well, and some of them had alters of fruit and bread as an offering of thanks for the harvest. |

| Alex and Kendall and I enjoyed this amazing cultural experience in our Indigenous outfits. |

The hosts of each home offered large platters of food to the groups to eat with our hands- usually white corn (called mote), chicken, pork or potatoes.

|

| Sometimes, the musicians would stop in the middle of the street and the circle would form around and around them again. |

Lyssa

Wow! I love this window into another culture, and your very personal experience with it. Thank you!

Unknown

a great ecuadorian tradition <3